JMTS 014: The Whole Town Can Be Your Hotel

Mission-driven hospitality and a trip to the public bathhouse in "Old Tokyo."

A few days before I check into Hanare, I receive a message asking if I would be interested in joining a free walking tour of the neighborhood.

A hotel offering a walking tour? That’s a first for me. But what a wonderful idea. Without hesitation, I sign up.

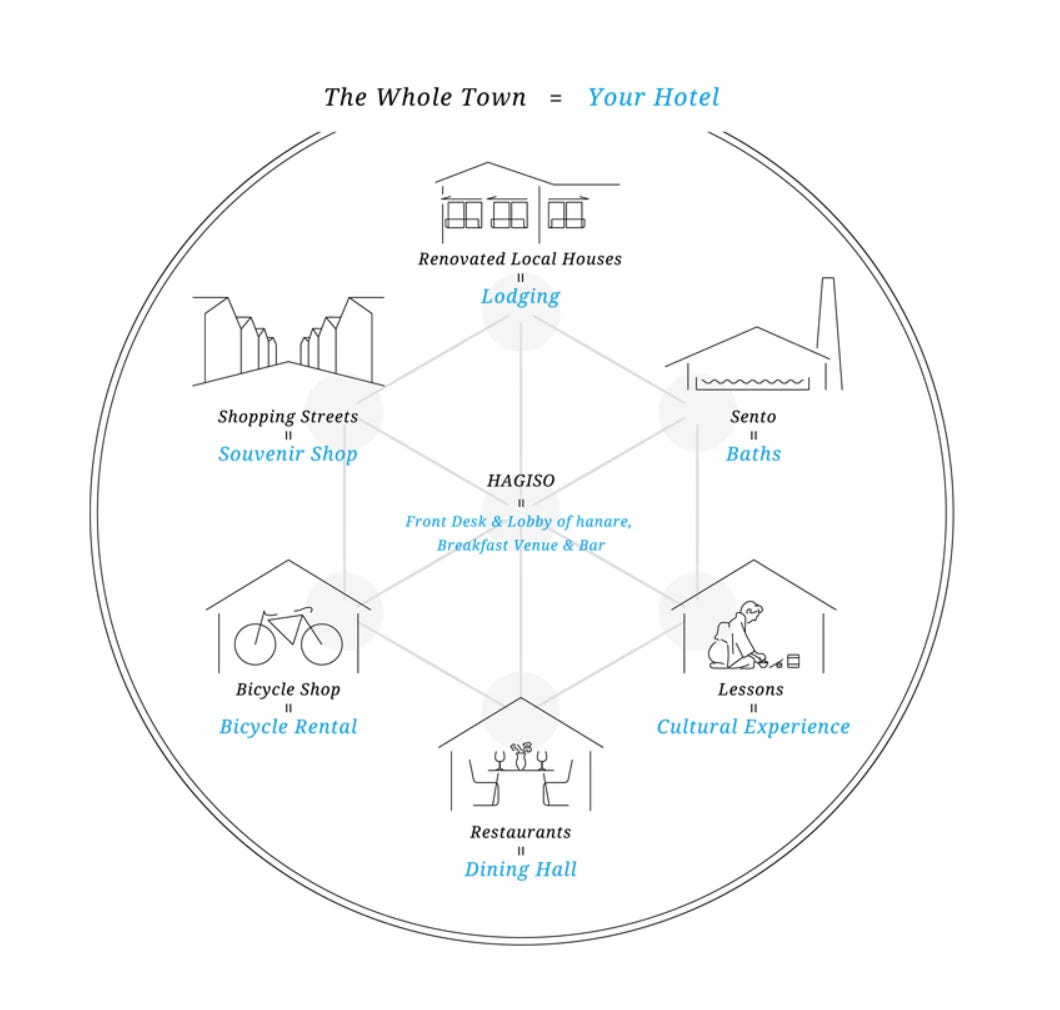

Hanare is a ‘decentralized’ or ‘scattered’ hotel located in the Yanaka district of Northeast Tokyo. The functions of the hotel — reception, lodging, breakfast — are physically spread out in different buildings in the town. The aim is to provide one-of-a-kind experiences for their guests, by thoughtfully connecting travelers to the neighborhood and local businesses. As encapsulated by Hanare’s tagline: “The whole town can be your hotel.”

In contrast to the ‘walled compound’ style of hotel or resort, where everything you need is at your fingertips and the objective of the hotel is to keep you — and your dollars — within the property, decentralized hotels are a model of mission-driven hospitality designed to benefit an entire community.

Tokyo, the largest city in the world, can feel impenetrable and unknowable. The last few places I’ve stayed (in Hamamatsu and Takanawa) were convenient to transportation, but felt cold and impersonal because nobody seemed to actually live there.

Hanare — and the decentralized hotel concept — offer a different way in. That’s what I’m hoping, anyway, as I make my way towards Tokyo.

I get a bit turned around exiting Nippori station on the JR Yamanote line, but eventually I sort it out, and walk ten minutes or so to my destination. I find reception up on the second floor and receive a warm welcome.

Over tea and cookies, my host and “concierge,” Momo, reviews the unique way things work here. The building we’re in is the hub of the hotel, housing the reception, the restaurant where I’ll be having breakfast, and a gallery. The lodging is located a few minutes walk down a residential road. And then there are three different public bathhouses - sento - to choose from, all within a 15 minute walk from the lodging.

As Momo hands me entrance tickets for the sento, she enthusiastically describes their distinguishing characteristics — the closest one is really hot, she warns me, even for Japanese people; there’s another one that has wonderful interior design. We’re having this conversation as we circle spots on a beautifully designed map of the area — one side a “Day Map” featuring shops, cafes, and museums, the other side a “Night Map” highlighting restaurants and bars.1 Already, I feel better oriented and more equipped with personal recommendations than most places I’ve stayed.

But it’s only the beginning. Because after our meeting, we drop off my bags at the lodging, and head out on our walking tour.

Often referred to as “Old Tokyo,” Yanaka is the only district in Tokyo that was not leveled by the Kanto earthquake in 1923, nor bombed by the Americans during World War II. It has a distinctive village-like atmosphere, with narrow residential alleyways, old cemeteries and rice cracker shops, all co-existing with modern coffee shops and boutiques.

As we chat and stroll, Momo leads me on a loop through the neighborhood. The main retail drag is called Yanaka Ginza, a well-known ‘retro shopping street’ with about 60 shops that flourished in post-war Japan. Though uniquely Japanese and pedestrian only, it conjures the same kind of nostalgia as “Main Street, USA,” with its old-fashioned, non-corporate vibe. Small businesses run by hard-working citizens. Local, self-sufficient, close-knit.

Momo shows me her favorite restaurants, points out the location of the supermarket and the entrance to metro, and introduces me to a charming shop selling handmade paper, called Isetatsu.

Since I mentioned that I was looking for green tea, she shows me where to buy some. We chat at length about an old shop that sells nothing but rice. She points out a line of girls in school uniforms outside a popular sweets stand selling imagawayaki, pancakes shaped like hockey pucks and filled with sweet bean paste.

As we make our way back to Hanare, Momo takes a shortcut, leading me down a residential back alleyway no wider than a vehicle. The space is further crowded by parked bicycles and loads of potted plants, these little micro-gardens that flourish improbably in the sliver of space between home and pavement. We stop, as is Momo’s custom, and say hello to someone’s pet turtles.

This is the ‘tourist attraction’ Momo is most keen to share with me: daily life in Yanaka.

Upon entering Marukoshi-so, the accommodation building, I remove my shoes and store them in a little shoe locker labeled with the name of my room: Kasumi. It’s a renovated apartment building from the 1960s that has been converted into five guest rooms. There are private toilets down the hall (one for each room), and a shared bath.

My room could certainly be described as minimalist. A small entry area also functions as a closet and a place to store my luggage. I slide open the fusama screen to step up into a Japanese-style room with a tatami mat floor. There’s a folded foam mattress and duvet (to be laid out at bedtime), a seating cushion, a beautifully designed wooden box of amenities that doubles as a table, and a globe light for a little ambiance. That’s basically it.

Traveling in Italy, you might put a premium on “a room with a view,” but in dense urban areas in Japan views can be pretty hard to come by.2 The buildings are just too close together, and windows are often mere inches from the street. Frosted glass is ubiquitous. I don’t love that I can’t see out, but the moment I feel a bicycle whiz past me just on the other side of the window, I appreciate that the world can’t see in. You begin to understand something about Japanese culture when you experience this kind of spatial proximity.

I open the Paulownia wood box, lifting off layers like a tiered bento box to reveal a treasure chest of amenities. There’s the typical stuff like soap and a toothbrush. But also, a hand-dyed tenegui multi-purpose towel, a staple of the Japanese home. There’s a simple little blank journal and pencil to record my observations. And a “recommended place” form to fill out, should I wish to add my own discoveries to a binder of recommendations for future guests.

Woven throughout Hanare are these gentle nudges to explore, notice, uncover. It’s palpable, this earnest desire that visitors engage with the community and culture in a meaningful and intentional way. Even the simplicity of the room seems to reinforce the message that the experience you came for is “out there” somewhere, beyond the frosted glass walls of the room.

In the evening twilight, I head back out on the town. “Travelers can find themselves in a place without pretense,” promises Hanare. And it’s true. It feels like a neighborhood of “regular” people — shopkeepers chatting with their customers, parents bringing their kids home from school, couples on dates. At Momo’s suggestion, I have dinner at a simple restaurant that serves rice balls and soup, Onigiri Café Risaku. At the table next to me, a mother tries to cajole her two young children into eating their vegetables. A moment that’s entirely specific to this place and, at the same time, utterly universal.

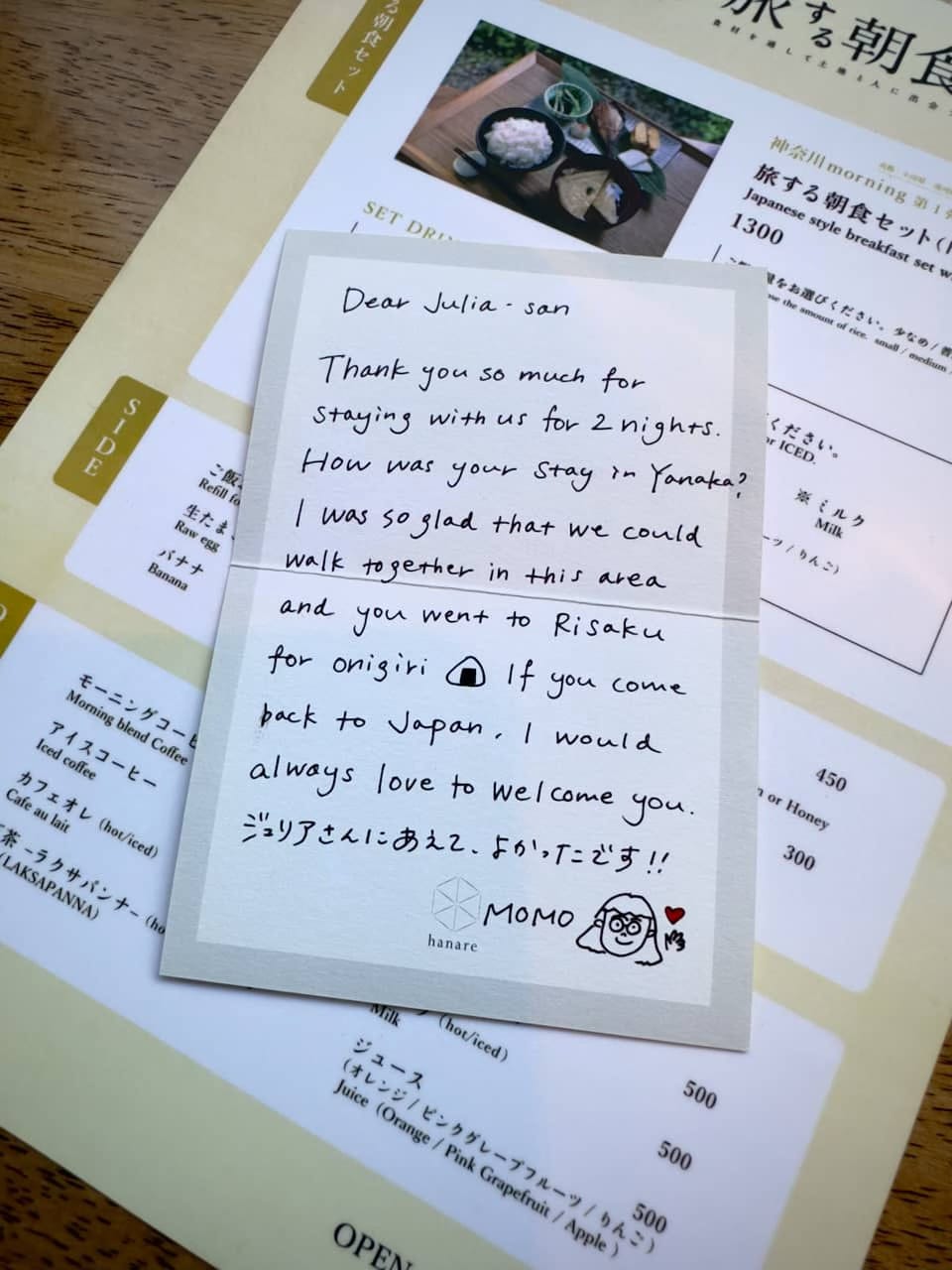

The next morning, I head back to the ground floor of the reception building for breakfast. It’s early and there aren’t many customers, but the few who trickle in are locals. It doesn’t feel like a ‘hotel restaurant’ because, well, there’s not really a ‘hotel.’ As I enjoy a classic Japanese breakfast of rice, soup, and fish, I notice a slip of paper on my tray detailing the background music playlist, titled “Good Morning Ears.” Studying it further, I see that the curator of today’s playlist is my friend Momo from the walking tour. “Oh! I know her!” I realize with a pleasant jolt of recognition. I’m beginning to feel right at home here.

I spend the day elsewhere in Tokyo, but on my way back to Hanare that afternoon, I drop by reception to say hello to Momo. Her playlist includes a song I happen to love, “Just The Two of Us,” covered by Fujii Kaze. I’d also read in her bio that her ‘special skills’ are singing and walking, and I tell her that I love singing and walking, too! We laugh and simultaneously burst into song, singing “Just The Two of Us” and dancing and grooving around the reception.

That night I decide to give the public bathhouse a go. I opt to use my ticket at Saito-yu, one of the longest-operating public baths in Tokyo. (If you’re wondering what the inside of a sento looks like, check out this video of Saito-yu, or stream the movie Perfect Days.) I pack some toiletries and a towel in a tote bag provided by Hanare and set off.

Public bathhouses in Tokyo are rapidly disappearing, due to changing lifestyles, aging customers, and aging owners, who often can’t find a successor when they thrown in the towel. In the last fifteen years alone, the number of sento in Tokyo has decreased by nearly half.

So entering the women’s locker room, I’m surprised to find that it’s packed. It’s Saturday night in Tokyo! There are grannies from the neighborhood. There are younger women with their gal pals. There are multi-generational family groups - Grandma, Mom, young daughter - here for some family bonding in the buff.

After World War II, sento were a necessity as many homes did not have bathing facilities. But now, a trip to a bathhouse is more of a leisure activity, or a chance for lonely old ladies to socialize, or a way to enjoy a nice soak without the bother of scrubbing the tub.

I feel a little awkward, but I manage to store my clothes in a locker, grab a plastic stool and bucket, and wash myself at one of the seated showers lining the wall. Once clean, I choose the least crowded looking bath, and ease myself in. It’s hotter than a hot tub, but not unbearable, and I sigh as my suitcase-schlepping muscles let go. Then I do my best to relax as I try to figure out how not to stare at the person sitting across from me.

There’s an expression in Japanese that goes something like: “To understand the town, go to the bathhouse.” It’s where a visitor can pick up on the local dialect, or the personality of a place, or generally get a read on the vibe. It’s surprisingly social. Personally, I’m feeling too shy and exposed to strike up a conversation with a stranger. But I can understand how the culture of the sento fosters a unique kind of intimacy with your neighbors. Everybody’s naked, after all. Without mask or artifice. In it together.

On my slow walk back to Hanare, feeling relaxed and flushed and drowsy, I suddenly realize that I can hear someone singing. I pause for a moment outside the closed door of what must be a karaoke bar. A man croons a ballad with so much feeling I can taste it. Audible but invisible, anonymous but emotional, just on the other side of that wall.

On the morning I check out, there’s a note from Momo delivered with my breakfast. I’m sure she writes one for every guest, but still, it feels personal and sincere, and I’m grateful. Thanks in no small part to Momo, Hanare delivered on its promise. I experienced the daily life of the town. I ate wonderful food. I got naked with strangers. And I made a new friend.

I’m sorry I’m not staying longer. But before I need to leave to catch my train, I’ve got just enough time to say goodbye to the turtles and go get one of those sweet bean paste-filled pancakes.

hanare (Reception inside HAGISO)

Address: 3 Chome-10-25 Yanaka, Taito City, Tokyo 110-0001, Japan (Google map)

Phone: +81-358347301

Website: https://hanare.hagiso.jp/en/

Rates: From $127/night for single occupancy or $161/night double occupancy, including breakfast, on Booking.com

Access: JR Nippori Station, West Exit (JR Yamanote Line & Keisei Skyliner from Narita Airport), OR Sendagi Station Exit 2 (Tokyo Metro Chiyoda Line.)

What do you think of the ‘decentralized hotel’ concept? Have you ever stayed in a hotel that offered a walking tour? Would you take advantage of an opportunity to visit a sento? Please reply to this email or - better yet! - respond in the comments. I absolutely love hearing from you. Thanks so much for being here.

👋 O genki de ne,

Julia Morrison

The map includes “Tips For Walking Around Town”, e.g., greeting locals as you walk around, being considerate of people’s privacy when taking photos, taking your garbage with you. The more you pay attention, the more you’ll notice just how often Japan is entreating the traveler to please have better manners. I suspect most of these admonitions fall on deaf ears. But as Hanare points out: “We all take care of the town.” As visitors, we can do better.

Unless, of course, you’re staying somewhere like the Park Hyatt Tokyo (where Lost In Translation was filmed) which occupies the top 14 floors of a 52-story building.

I really want to stay there!! A compelling article.

It sounds amazing. The opportunity to get away and get to really know a place in a deeper way - that’s my kind of travel. We could all do with a few more Momo’s in our lives, too.